I am the author of iOS 17 Fundamentals, Building iOS User Interfaces with SwiftUI, and eight other courses on Pluralsight.

Deepen your understanding by watching!

How Delegation Works – A Swift Developer’s Guide

Updated on October 11, 2016 – Swift 3.0

Delegation can be a difficult topic to wrap your head around. I found it easiest to break up posts on the topic to help readers who are new to the pattern grasp the concepts a little better. First, I analyzed what delegation is in “What is Delegation – A Swift Developer’s Guide”. If you’re looking for the “what is it?” behind the “how does it work?”, I recommend giving that first article a read.

Once the terminology is unpacked and a high-level overview of delegation as a design pattern is understood, the next logical place to turn is to the question, “How does delegation work?”. That is the focus of this article.

Introducing the players

For delegation to occur in software, you’d have a situation where one class (a delegat_or_ class) would give control or responsibility for some behavioral logic to another class called a delegate.

So how does one class delegate behavioral logic to another class? With iOS and Swift, the delegation design pattern is achieved by utilizing an abstraction layer called a protocol.

A protocol defines a blueprint of methods, properties, and other requirements that suit a particular task or piece of functionality.

Protocols as abstractions

I used the fancy term “abstraction layer” prior to the quote. What is that all about?

Protocols are an “abstraction”, because they do not provide implementation details in their declaration… Only function and property names. Like an outline, or as Apple puts it, a blueprint.

Protocols as blueprints

With a single blueprint, there can be many homes constructed. The fine details of their construction may differ, but in the end, houses of some similarity that satisfy the blueprint’s specifications are built.

So, too with a protocol: Many classes can be built that follow the protocol’s specifications. At the end of the day, the fine details of each class’ implementation (the stuff between the curly braces { ... }) may differ, but if they adopt the protocol, they’ll be similar in at least the fact that they provide the named behavior it specified.

Protocols as contracts

Another analogy from the legal world is popular for describing protocols: Protocols are similar to contracts. It’s this contractual idea that actually makes the most sense to me when it comes to delegation.

A contract is the “thing” in the middle of two parties who are trying to negotiate a deal. To one party, the contract is a guarantee of some terms that will be satisfied. To the other party, the contract is a set of obligations.

In the delegation design pattern, protocols serve the same kind middle-man role as a contract. To the delegat_or_ class, the protocol is a guarantee that some behavior will be supplied by the other party (the delegate). To the delegate class, the protocol is a set of obligations – things it must implement when it “signs the contract”, or in Swift terms, “adopts the protocol”.

While the person signing the contract probably gets something out of the deal, the focus in the analogy we’re making to protocols and the delegation pattern is on the person on the guarantee end.

That person, being guaranteed by the contract that certain terms will be executed by the person who signs the deal, is free to make decisions and take action based on that promise.

So, too with the class delegating to another class. The delegat_or_ class can make perform actions (call methods defined by the protocol) or make decisions (access properties defined by the protocol to use in its logic).

Listing the players

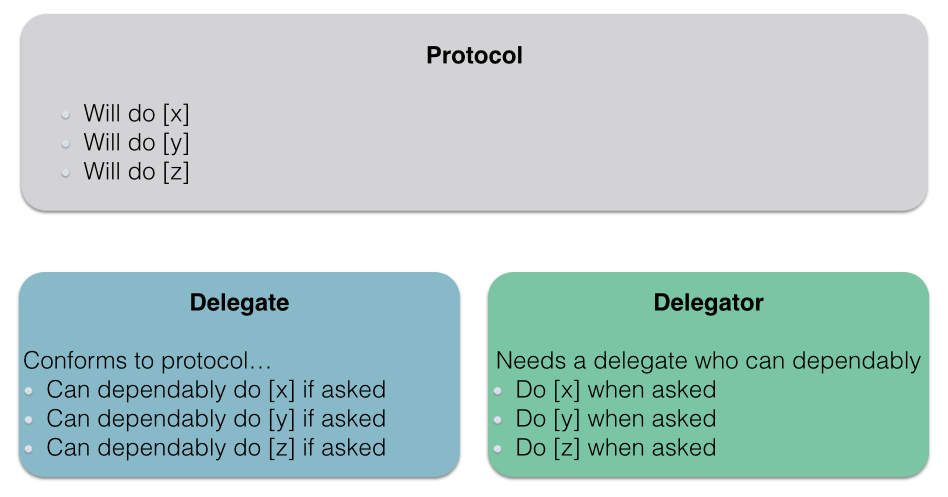

Stepping back from this description, we see three players involved:

- A protocol defining the responsibilities that will be delegated

- A delegat_or_, which depends on an instance of something conforming to that protocol

- A delegate, which adopts the protocol and implements its requirements

Visualize the players

As you can see, there are a few moving parts to delegation. Sometimes it helps to visualize the players involved in the strategy. I created the following diagram for an analysis I wrote on NSNotificationCenter vs Delegation, but I think it gets the point across for this blog entry as well:

An example in code

Hopefully the explanation so far has provided some good groundwork to sort out how to accomplish the delegation design pattern in code. So how does it all get wired up?

Setting up the delegator

A delegat_or_ class typically defines a variable property with the word “delegate” somewhere in the name (oftentimes the property is simply named delegate if that’s explanatory enough). The Type of the variable property is the key to it all. The variable will be of Type whatever-you-named-your-delegate-protocol. So if I named my protocol MySpecialDelegate, I’d specify the Type of the delegate property to be MySpecialDelegate.

Setting up the delegate

The delegate class is what adopts the protocol and implements its requirements. In the class declaration, the name of the protocol(s) that the class intends to adopt are listed separated by commas after the name of the superclass (if the class inherits from a superclass):

class MyClass: SuperClass, Protocol1, Protocol2 { ... }

When the delegat_or_ class gets initialized, a second step is often to immediately assign an instance of the class that’s adopted the delegate protocol to its delegate property so that everything is “wired up”.

Delegation in practice

Working with the delegation pattern in practice usually involves interacting with the protocol from the delegate end of things. Most of the time, we’re working with Apple’s APIs (such as a UITableView or just about any other UI control they provide). We typically only require knowledge of the protocol’s definition so that the class we choose as our delegate can implement the right functions.

Complete example

There may be some situations where you may decide to follow Apple’s lead and use the delegation design pattern for your own code. Maybe you’re making a special UIView subclass or a special picker control (much like UIImagePickerController). Or maybe you’re into game development and would like to communicate from your SKScene back to the View Controller. These are just a few that came to mind, but they all present possibilities for utilizing the delegation strategy.

To give a simple example, suppose that we’ve decided to create a class to encapsulate all of the logic for a special rating picker control. We’d like to offer the ability to customize the picker some by allowing the user of our control to specify a preferred rating symbol. We’d also like to provide a feedback loop to notify the user of our control when certain events have occurred. Delegation is a great tool to provide both customization options and communication between classes. What would this example look like in code?

Create the protocol

First, the protocol:

1protocol RatingPickerDelegate {

2 func preferredRatingSymbol(picker: RatingPicker) -> UIImage?

3 func didSelectRating(picker: RatingPicker, rating: Int)

4 func didCancel(picker: RatingPicker)

5}

Notice how this protocol definition allows both the customization point and the feedback loop we were hoping for. It’s always nice for the delegate to have access to the public API of the instance calling its methods, so the RatingPicker (or UITableView or UIScrollView or whatever) is often passed along as an argument.

Create the delegator

With the protocol defined, our RatingPicker (the delegat_or_ in this case) can now set itself up to use that protocol:

1// Disclaimer: There is much more logic that would go into a real UIView subclass or a picker control in real life

2// This example is contrived and is only meant to serve as a "shell" of what code could look like

3// that uses a delegate within its implementation

4

5class RatingPicker {

6 weak var delegate: RatingPickerDelegate?

7

8 init(withDelegate delegate: RatingPickerDelegate?) {

9 self.delegate = delegate

10 }

11

12 func setup() {

13 let preferredRatingSymbol = delegate?.preferredRatingSymbol(picker: self)

14

15 // Set up the picker with the preferred rating symbol if it was specified

16 }

17

18 func selectRating(selectedRating: Int) {

19 delegate?.didSelectRating(picker: self, rating: selectedRating)

20 // Other logic related to selecting a rating

21 }

22

23 func cancel() {

24 delegate?.didCancel(picker: self)

25 // Other logic related to canceling

26 }

27}

The delegate property is strongly typed to be a RatingPickerDelegate.

Since it’s optional here in this implementation, the delegate is not absolutely essential for the RatingPicker to work. If it were essential, we’d parameterize init and assign it during initialization.

I’ve used optional chaining to get at the delegate's methods if the delegate isn’t nil.

Choosing the delegate

Choosing the delegate class is the final decision to make. It’s not uncommon for a View Controller to take up the responsibility of being a delegate. In “Pick a Delegate, Any Delegate”, I attempted to show how it’s not necessary to use the View Controller as your one stop delegate shop. For this example, I’ll avoid giving the View Controller more responsibility than it needs and I’ll create a simple handler class to assume the delegated responsibilities:

1class RatingPickerHandler: RatingPickerDelegate {

2 func preferredRatingSymbol(picker: RatingPicker) -> UIImage? {

3 return UIImage(contentsOfFile: "Star.png")

4 }

5

6 func didSelectRating(picker: RatingPicker, rating: Int) {

7 // do something in response to a rating being selected

8 }

9

10 func didCancel(picker: RatingPicker) {

11 // do something in response to the rating picker canceling

12 }

13}

Wrapping up

Once the terminology of delegation is unpacked, understanding how it works is the next logical step for grasping the design pattern as a whole. Here we explored all the players involved in the strategy and related protocols, which are integral to the strategy, to some real-world analogies. Finally, we took a look at how delegation works in practice, and demonstrated each role in delegation with code.